"A large part of the present anxiety to improve the education of girls and women is also due to the conviction that the political disabilities of women will not be maintained." ~Millicent Fawcett

Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the daughter Newson Garrett and Louise Dunnell, was born in Aldeburgh, Suffolk in 1847. When she was twelve years old, her older sister, Elizabeth Garrett, moved to London in an attempt to qualify as a doctor. Millicent's visits to London to stay with her older sister Elizabeth and other sister, Louise, brought her into contact with people with radical political views. In 1865 Louise took Millicent to hear a speech on women's rights made by the Radical MP, John Stuart Mill. Millicent was deeply impressed by Mill and became one of his many loyal supporters.

Mill introduced Millicent to other campaigners for women's rights. This included Henry Fawcett, the Radical MP for Brighton. Fawcett, who had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1857, had been expected to marry Millicent's sister Elizabeth, but in 1865 she decided to concentrate of her attempts to become a doctor. Henry and Millicent became close friends and even though she was warned against marrying a disabled man, 14 years her senior, the couple was married in 1867. On 4 Apr 1868 their daughter, Philippa Fawcett, was born.

Over the next few years Millicent spent much of her time assisting Henry in his work as a MP However, Henry, an ardent supporter of women's rights, encouraged Millicent to continue her own career as a writer. At first Millicent wrote articles for journals but later books such as Political Economy for Beginners and Essays and Lectures on Political Subjects were published.

Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee in 1868. Although only a moderate public speaker, Millicent was a superb organizer and eventually emerged as the one of the leaders of the suffrage movement. She was so nervous before a speech that she was often physically ill. As a result she refused to make speeches more than four times a week.

She also campaigned against the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act: "In 1857 the Divorce Act was passed, and, as is well known, set up by law a different moral standard for men and women. Under this Act, which is still in force, a man can obtain the dissolution of the marriage if he can prove one act of infidelity on the part of his wife; but a woman cannot get her marriage dissolved unless she can prove that her husband has been guilty both of infidelity and cruelty."

Millicent also took a keen interest in women's education. She was involved in the organization of women's lectures at Cambridge that led to the establishment of Newnham College. Philippa Fawcett, went to Newnham and was placed first in the mathematical tripos.

The political career of Henry Fawcett was also going well. In 1880 William Gladstone, leader of the Liberal government, appointed Henry as his Postmaster General. Henry, who introduced the parcel post, postal orders and the sixpenny telegram, also used his power as Postmaster General to start employing women medical officers.

Henry was taken seriously ill with diphtheria and, although he gradually recovered, his political career had come to an end. Severely weakened by his illness, he died of pleurisy on 6 Nov 1884. It was claimed that "even decades later she would be visibly distressed by the mention of her husband's name."

Millicent now had more time for her own political career and became involved with the Personal Rights Association, which took an active role in exposing men who preyed on vulnerable young women. In 1886 she took part in a physical assault on an army major who had been pestering a servant of a friend of hers. According to William Stead: "They threw flour over his waxed moustache and in his eyes and down the back of his neck. They pinned a paper on his back, and made him the derision of a crowded street... in the sequel he was turned out of a club, and cut by a few lady friends - among them a young lady of some means to whom he was engaged at the time when he planned to ruin the country lass. Mrs Fawcett had no pity; she would have cashiered him if she could."

After the death of Lydia Becker in 1890, Millicent was elected president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She believed that it was important that the NUWSS campaigned for a wide variety of causes. This included helping Josephine Butler in her campaign against white slave traffic. Millicent also gave support to Clementina Black and her attempts to persuade the government to help protect low paid women workers.

Millicent's sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, joined the WSPU. In December, 1911 she wrote to her sister: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

Although Millicent had always been a Liberal, she became increasing angry at the party's unwillingness to give full support to women's suffrage. Herbert Asquith became Prime Minister in 1908. Unlike other leading members of the Liberal Party, Asquith was a strong opponent of votes for women. In 1912 Fawcett and the NUWSS took the decision to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary elections.

Despite Asquith's unwillingness to introduce legislation, Millicent remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. Like other members of the NUWSS, she feared that the militant actions of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) would alienate potential supporters of women's suffrage. However, Fawcett admired the courage of the suffragettes and was restrained in her criticism of the WSPU.

Millicent was upset when Louisa Garrett Anderson was sent to prison for taking part in the window-braking campaign. She wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does."

Mill introduced Millicent to other campaigners for women's rights. This included Henry Fawcett, the Radical MP for Brighton. Fawcett, who had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1857, had been expected to marry Millicent's sister Elizabeth, but in 1865 she decided to concentrate of her attempts to become a doctor. Henry and Millicent became close friends and even though she was warned against marrying a disabled man, 14 years her senior, the couple was married in 1867. On 4 Apr 1868 their daughter, Philippa Fawcett, was born.

Over the next few years Millicent spent much of her time assisting Henry in his work as a MP However, Henry, an ardent supporter of women's rights, encouraged Millicent to continue her own career as a writer. At first Millicent wrote articles for journals but later books such as Political Economy for Beginners and Essays and Lectures on Political Subjects were published.

Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee in 1868. Although only a moderate public speaker, Millicent was a superb organizer and eventually emerged as the one of the leaders of the suffrage movement. She was so nervous before a speech that she was often physically ill. As a result she refused to make speeches more than four times a week.

She also campaigned against the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act: "In 1857 the Divorce Act was passed, and, as is well known, set up by law a different moral standard for men and women. Under this Act, which is still in force, a man can obtain the dissolution of the marriage if he can prove one act of infidelity on the part of his wife; but a woman cannot get her marriage dissolved unless she can prove that her husband has been guilty both of infidelity and cruelty."

Millicent also took a keen interest in women's education. She was involved in the organization of women's lectures at Cambridge that led to the establishment of Newnham College. Philippa Fawcett, went to Newnham and was placed first in the mathematical tripos.

The political career of Henry Fawcett was also going well. In 1880 William Gladstone, leader of the Liberal government, appointed Henry as his Postmaster General. Henry, who introduced the parcel post, postal orders and the sixpenny telegram, also used his power as Postmaster General to start employing women medical officers.

Henry was taken seriously ill with diphtheria and, although he gradually recovered, his political career had come to an end. Severely weakened by his illness, he died of pleurisy on 6 Nov 1884. It was claimed that "even decades later she would be visibly distressed by the mention of her husband's name."

Millicent now had more time for her own political career and became involved with the Personal Rights Association, which took an active role in exposing men who preyed on vulnerable young women. In 1886 she took part in a physical assault on an army major who had been pestering a servant of a friend of hers. According to William Stead: "They threw flour over his waxed moustache and in his eyes and down the back of his neck. They pinned a paper on his back, and made him the derision of a crowded street... in the sequel he was turned out of a club, and cut by a few lady friends - among them a young lady of some means to whom he was engaged at the time when he planned to ruin the country lass. Mrs Fawcett had no pity; she would have cashiered him if she could."

After the death of Lydia Becker in 1890, Millicent was elected president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She believed that it was important that the NUWSS campaigned for a wide variety of causes. This included helping Josephine Butler in her campaign against white slave traffic. Millicent also gave support to Clementina Black and her attempts to persuade the government to help protect low paid women workers.

Millicent's sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, joined the WSPU. In December, 1911 she wrote to her sister: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

Although Millicent had always been a Liberal, she became increasing angry at the party's unwillingness to give full support to women's suffrage. Herbert Asquith became Prime Minister in 1908. Unlike other leading members of the Liberal Party, Asquith was a strong opponent of votes for women. In 1912 Fawcett and the NUWSS took the decision to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary elections.

Despite Asquith's unwillingness to introduce legislation, Millicent remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. Like other members of the NUWSS, she feared that the militant actions of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) would alienate potential supporters of women's suffrage. However, Fawcett admired the courage of the suffragettes and was restrained in her criticism of the WSPU.

Millicent was upset when Louisa Garrett Anderson was sent to prison for taking part in the window-braking campaign. She wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does."

|

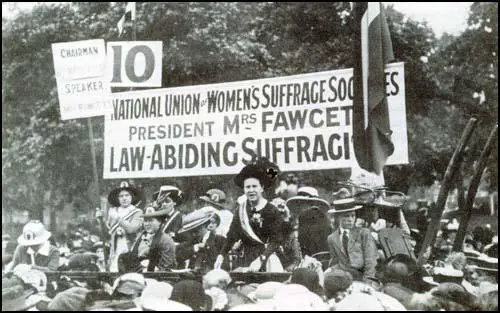

Millicent Fawcett addressing the crowds in

Hyde Park at the culmination of the Pilgrimage on

26 Jul 1913.

|

Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4 Aug 1914, the NUWSS declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although Millicent supported the First World War effort she did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. Fran Abrams has pointed out: "She (Millicent Fawcett) would lose no fewer than twenty-nine members of her extended family, including two nephews."

Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Millicent refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace."

After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Chrystal Macmillan, Margaret Ashton, Kathleen Courtney, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

Kathleen Courtney wrote when she resigned: "I feel strongly that the most important thing at the present moment is to work, if possible on international lines for the right sort of peace settlement after the war. If I could have done this through the National Union, I need hardly say how infinitely I would have preferred it and for the sake of doing so I would gladly have sacrificed a good deal. But the Council made it quite clear that they did not wish the union to work in that way."

According to Elizabeth Crawford, author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Mrs. Fawcett afterwards felt particularly bitter towards Kathleen Courtney, whom she felt had been intentionally and personally wounding, and refused to effect any reconciliation, relying, as she said, on time to erase the memory of this difficult period."

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Mary Sheepshanks, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Emily Bach, Lida Gustava Heymann, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Kathleen Courtney, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan and Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WIL).

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the NUWSS and WSPU disbanded. A new organisation called the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship was established. As well as advocating the same voting rights as men, the organisation also campaigned for equal pay, fairer divorce laws and an end to the discrimination against women in the professions.

Women had their first opportunity to vote in a General Election in December, 1918. Several of the women involved in the suffrage campaign stood for Parliament. Only one, Constance Markiewicz, standing for Sinn Fein, was elected. However, as a member of Sinn Fein, she refused to take her seat in the House of Commons. Later that year, Nancy Astor became the first woman in England to become a MP when she won Sutton, Plymouth in a by-election. Other women were also elected over the next few years. This included Dorothy Jewson, Susan Lawrence, Margaret Winteringham, Katharine Stewart-Murray, Mabel Philipson, Vera Terrington and Margaret Bondfield.

In 1919 Parliament passed the Sex Disqualification Removal Act which made it illegal to exclude women from jobs because of their sex. Women could now become solicitors, barristers and magistrates. Millicent ceased to be active in politics and concentrated on writing books such as The Women's Victory (1920), What I Remember (1924) and Josephine Butler (1927).

A bill was introduced in March 1928 to give women the vote on the same terms as men. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2 Jul 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. Many of the women who had fought for this right were now dead including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pankhurst.

Millicent had the pleasure of attending Parliament to see the vote take place. That night she wrote in her diary: "It is almost exactly 61 years ago since I heard John Stuart Mill introduce his suffrage amendment to the Reform Bill on May 20th, 1867. So I have had extraordinary good luck in having seen the struggle from the beginning."

Millicent Fawcett died on 5 Aug 1929.

No comments:

Post a Comment