Friday, January 31, 2014

Timeline of the Women's Rights Movement

Timeline of the Women's Rights Movement in the U.S.

1777~1984

- 1777 ~ The original 13 states pass laws that prohibit women from voting. Abigail Smith Adams, wife of President John Adams, writes that women "will not hold ourselves bound by any laws which we have no voice."

- 1826 ~ The first public high schools for girls open in New York and Boston. The American Journal of Education wrote that the school should give "women such an education as shall make them fit wives for well educated men, and enable them to exert a salutary influence upon the rising generation."

- 1833 ~ Oberlin College is founded in Ohio and becomes the first college to admit women and African Americans. The Oberlin Collegiate Institute held as one of its primary objectives: "the elevation of the female character, bringing within the reach of the misjudge and neglected sex, all the instructive privileges which hitherto have unreasonably distinguished the leading sex from theirs." While women took courses with men, they pursued diplomas from the Ladies Course. Three women graduated in 1841.

- 1837 ~ Mary Lyon establishes Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, the first college for women.

- 1848 ~ The world's first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, NY, July 19-20. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women.

- 1849 ~ Elizabeth Smith Miller appears on the streets of Seneca Falls, NY,in "turkish trousers," soon to be known as "bloomers."

- 1849 ~ Amelia Jenks Bloomer publishes and edits Lily, the first prominent women's rights newspaper.

- 1849 ~ Elizabeth Blackwell becomes the first woman to receive a medical degree in the U.S. from Geneva College in New York. For the first time, women are permitted to practice medicine legally.

- 1850 ~ Quaker physicians establish the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, PA to give women a chance to learn medicine. The first women graduated under police guard.

- 1850 ~ The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, MA, attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860.

- 1855 ~ Lucy Stone becomes first woman on record to keep her own name after marriage, setting a trend among women who are consequently known as "Lucy Stoners."

- 1855 ~ The University of Iowa becomes the first state school to admit women.

- 1855 ~ In Missouri v. Celia, a Black slave is declared property without right to defense against a master's act of rape.

- 1859 ~ American Medical Association announces opposition to abortion. In 1860, Connecticut is the first state to prohibit all abortions, both before and after quickening.

- 1859 ~ The birth rate continues its downward spiral as reliable condoms become available. By the late 1900s, women will raise an average of only two or three children.

- 1860 ~ Of 2,225,086 Black women, 1,971,135 are held in slavery. In San Francisco, about 85% of Chinese women are essentially enslaved as prostitutes.

- 1866 ~ The 14th Amendment is passed by Congress (ratified by the states in 1868), the first time "citizens" and "voters" are defined as "male" in the Constitution.

- 1866 ~ The American Equal Rights Association is founded, the first organization in the U.S. to advocate women's suffrage.

- 1868 ~ The National Labor Union supports equal pay for equal work.

- 1868 ~ Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony begin publishing The Revolution, an important women's movement periodical.

- 1869 (May) ~ Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution.

- 1869 (Nov) ~ Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell and others form the American Woman Suffrage Association. This group focuses exclusively on gaining voting rights for women through amendments to individual state constitutions.

- 1869 (Dec. 10) ~ The territory of Wyoming passes the first women's suffrage law. The following year, women begin serving on juries in the territory.

- 1870 ~ Iowa is the first state to admit a woman to the bar: Arabella Mansfield.

- 1870 ~ The 15th Amendment receives final ratification. By its text, women are not specifically excluded from the vote. During the next two years, approximately 150 women will attempt to vote in almost a dozen different jurisdictions from Delaware to California.

- 1872 ~ Through the efforts of lawyer Belva Lockwood, Congress passes a law to give women federal employees equal pay for equal work.

- 1872 ~ Charlotte E. Ray, a Howard University law school graduate, becomes first African-American woman admitted to the U.S. bar.

- 1872 ~ Susan B. Anthony casts her first vote in an attempt to test whether the 14th Amendment would be interpreted broadly to guarantee women the right to vote. She was tried in June 17-18, 1873 in Canandaigua, NY and found guilty of "unlawful voting."

- 1873 ~ Bradwell v. Illinois: Supreme Court affirms that states can restrict women from the practice of any profession to uphold the law of the Creator.

- 1873 ~ Congress passes the Comstock Law, defining contraceptive information as "obscene material."

- 1874 (Oct 15) ~ Virginia Minor applies to register to vote in Missouri. The registrar, Reese Happersett, turned down the application, because the Missouri state constitution read: "Every male citizen of the United States shall be entitled to vote." Mrs. Minor sued in Missouri state court, claiming her rights were violated on the basis of the 14th Amendment. She argues that the 14th Amendment’s privileges and immunities clause must be interpreted to guarantee her a right to vote. However the Supreme Court rules that while women are "persons" under the 14th Amendment that they are a special category of "non-voting" citizens and that states remain free to grant or deny women the right to vote.

- 1877 ~ Helen Magill is the first woman to receive a Ph.D. at a U.S. school, a doctorate in Greek from Boston University.

- 1878 ~ The Susan B. Anthony Amendment, to grant women the vote, is first introduced in the U.S. Congress.

- 1884 ~ Belva Lockwood, presidential candidate of the National Equal Rights Party, is the first woman to receive votes in a presidential election (approx. 4,000 in six states).

- 1887 ~ For the first and only time in this century, the U.S. Senate votes on woman suffrage. It loses, 34 to 16. Twenty-five Senators do not bother to participate.

- 1890 ~ After several years of negotiations, the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association merge to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) the leadership of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Now the women's movement main organization, NAWSA works to obtain voting rights for women.

- 1893 ~ Colorado is the first state to adopt an amendment granting women the right to vote. Utah and Idaho follow suite in 1896; Washington State in 1910; California in 1911; Oregon, Kansas and Arizona in 1912; Alaska and Illinois in 1913; Montana and Nevada in 1914; New York in 1917; Michigan, South Dakota and Oklahoma in 1918.

- 1896 ~ The National Association of Colored Women is formed, bringing together more than 100 Black women's clubs. leaders in the Black women's club movement include Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Mary Church Terrell and Anita Julia Cooper.

- 1899 ~ National Consumers League is formed with Florence Kelley as its president. The League organizes women to use their power as consumers to push for better working conditions and protective laws for women workers.

- 1900 ~ Two-thirds of divorce cases are initiated by the wife; a century earlier, most women lacked the right to sue and were hopelessly locked into bad marriages.

- 1903 ~ Based on a similar organization in Britain, the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) is founded at the convention of the American Federation of Labor in Boston, when it became clear that American labor had no intention of organizing America's women into trade unions.The goals of the WTUL are to secure better occupational conditions and improved wages for women as well as to encourage women to join the labor movement. Local branches are quickly established in Boston, Chicago and New York.

- 1909 ~ Women garment workers strike in New York for better wages and working conditions in the Uprising of the 20,000. Over 300 shops eventually sign union contracts.

- 1912 ~ Juliette Gordon Low founds first American group of Girl Guides, in Atlanta, GA. Later renamed the Girl Scouts of the USA, the organization brings girls into the outdoors, encourages their self-reliance and resourcefulness and prepares them for varied roles as adult women.

- 1913 ~ Alice Paul and Lucy Burns form the Congressional Union to work toward the passage of a federal amendment to give women the vote. It later is renamed the National Women's Party. Members picket the White House and engage in other forms of civil disobedience, drawing public attention to the suffrage cause.

- 1914 ~ Margaret Sanger calls for legalization of contraceptives in her feminist publication, The Woman Rebel, which the Post Office bans from the mails.

- 1916 ~ Margaret Sanger opens the first U.S. birth control clinic in Brooklyn, NY. Although the clinic is shut down 10 days later and Sanger is arrested, she eventually wins support through the courts and opens another clinic in New York City in 1923.

- 1917 ~ During WWI women move into many jobs working in heavy industry in mining, chemical manufacturing, automobile and railway plants. They also run street cars, conduct trains, direct traffic and deliver mail.

- 1917 ~ Jeannette Rankin of Montana becomes the first woman elected to the U.S. Congress.

- 1919 ~ The federal woman suffrage amendment, originally written by Susan B. Anthony and introduced in Congress in 1878, is passed by the House of Representatives (304 to 89). The Senate passes it with just two votes to spare (56 to 25). It is then sent to the states for ratification.

- 1920 ~ The Women's Bureau of the Department of Labor is formed to collect information about women in the workforce and safeguard good working conditions for women.

- 1920 (Aug 26) ~ The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, granting women the right to vote, is signed into law by the Secretary of State, Bainbridge Colby.

- 1921 ~ Margaret Sanger organizes the American Birth Control League, which becomes Federation of Planned Parenthood in 1942.

- 1923 ~ Supreme Court strikes down a 1918 minimum-wage law for District of Columbia women because, with the vote, women are considered equal to men. This ruling cancels all state minimum wage laws.

- 1933 ~ Frances Perkins, the first woman in a Presidential cabinet, serves as Secretary of Labor during the entire Roosevelt presidency.

- 1936 ~ The federal law prohibiting the dissemination of contraceptive information through the mail is modified, and birth control information is no longer classified as obscene. The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second District renders an historic decision in U.S. v. One Package and asserts the rights of the physician in the legitimate use of contraceptives and eradicated the restrictions prohibiting the importation, sale or carriage by mail of contraceptive materials and information for medical purposes.

- 1941 ~ A massive government and industry media campaign persuades women to take jobs during the war. Almost 7 million women respond, 2 million as industrial "Rosie the Riveters" and 400,000 join the military.

- 1945 ~ Women industrial workers begin to lose their jobs in large numbers to returning service men, although surveys show 80% want to continue working.

- 1957 ~ The number of women and men voting is approximately equal for the first time.

- 1960 ~ The Food and Drug Administration approves birth control pills.

- 1960 ~ Women now earn only 60 cents for every dollar earned by men, a decline since 1955. Women of color earn only 42 cents.

- 1961 ~ President John Kennedy establishes the President's Commission on the Status of Women to explore issues relating to women and to make proposals in such areas as employment policy, education, and federal Social Security and tax laws relating to women. Kennedy appointed Eleanor Roosevelt, former U.S. delegate to the United Nations and widow of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, to chair the commission The report issued by the Commission in 1963 documents substantial discrimination against women in the workplace and makes specific recommendations for improvement, including fair hiring practices, paid maternity leave, and affordable child care.

- 1963 ~ The Equal Pay Act, proposed 20 years earlier, establishes equal pay for men and women performing the same job duties. It does not cover domestics, agricultural workers, executives, administrators or professionals.

- 1963 ~ Betty Friedan's best-seller, The Feminine Mystique, detailed the "problem that has no name." Five million copies are sold by 1970, laying the groundwork for the modern feminist movement.

- 1964 ~ Title VII of the Civil Rights Act bars employment discrimination by private employers, employment agencies and unions based on race, sex and other grounds. To investigate complaints and enforce penalties, it establishes the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which receives 50,000 complaints of gender discrimination in its first five years.

- 1966 ~ National Organization for Women (NOW) is formed by a group of feminists including Betty Friedan while attending the Third National Conference of Commissions on the Status of Women. It becomes the largest women's rights group in the United States, and begins working to end sexual discrimination, especially in the workplace, by means of legislative lobbying, litigation, and public demonstrations.

- 1967 ~ Executive Order 11375 (amending Executive Order 11246) expands President Lyndon Johnson's affirmative action policy of 1965 to cover discrimination based on gender. As a result, federal agencies and contractors must take active measures to ensure that women as well as minorities enjoy the same educational and employment opportunities as white males.

- 1968 ~ New York Radical Women garner media attention to the women's movement when they protest the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City.

- 1968 ~ The first national women's liberation conference is held in Chicago.

- 1968 ~ The National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL) is founded.

- 1968 ~ National Welfare Rights Organization is formed by activists such as Johnnie Tillmon and Etta Horm. They have 22,000 members by 1969, but are unable to survive as an organization past 1975.

- 1968 ~ Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) is first Black woman elected to the U.S. Congress.

- 1970 ~ Women's wages fall to 59 cents for every dollar earned by men. Although non-white women earn even less, the gap is closing between white women and women of color.

- 1970 ~ The Equal Rights Amendment is reintroduced into Congress.

- 1972 ~ Congress sends the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution to the states for ratification. Originally drafted by Alice Paul in 1923, the amendment reads: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." Congress places a seven year deadline on the ratification process, and although the deadline extends until 1982, the amendment does not receive enough state ratifications. It is still not part of the U.S. Constitution.

- 1972 ~ Title IX of the Education Amendments bans sex discrimination in schools. It states: "No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving federal financial assistance." As a result of Title IX, the enrollment of women in athletics programs and professional schools increases dramatically.

- 1973 ~ The first battered women's shelters open in the U.S., in Tucson, AZ and St. Paul, MN.

- 1973 ~ In Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court establishes a woman's right to abortion, effectively canceling the anti-abortion laws of 46 states.

- 1974 ~ MANA, the Mexican-American Women's National Association, organizes as feminist activist organization. By 1990, MANA chapters operate in 16 states; members in 36.

- 1974 ~ Hundreds of colleges are offering women's studies courses. Additionally, 230 women's centers on college campuses provide support services for women students.

- 1975 ~ The first women's bank opens, in New York City.

- 1978 ~ The Pregnancy Discrimination Act amends the Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and bans employment discrimination against pregnant women. Under the Act, a woman cannot be fired or denied a job or a promotion because she is or may become pregnant, nor can she be forced to take a pregnancy leave if she is willing and able to work.

- 1981 ~ At the request of women's organizations, President Carter proclaims the first "National Women's History Week," incorporating March 8, International Women's Day.

- 1981 ~ Sandra Day O'Connor is the first woman ever appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1993, she is joined by Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

- 1984 ~ Geraldine Ferraro is the first woman vice-presidential candidate of a major political party (Democratic Party).

Friday, January 24, 2014

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

"Oh, if I could but live another century and see the fruition of all the work for women! There is so much yet to be done." ~Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) is perhaps the most widely known suffragist of her generation and has become an icon of the woman’s suffrage movement. She traveled the country to give speeches, circulate petitions and organize local women’s rights organizations.

Susan was born in Adams, MA. After the Anthony family moved to Rochester, NY in 1845, they became active in the antislavery movement. Antislavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where they were sometimes joined by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Later two of Anthony's brothers, Daniel and Merritt, were anti-slavery activists in the Kansas territory.

In 1848 Susan was working as a teacher in Canajoharie, NY and became involved with the teacher’s union when she discovered that male teachers had a monthly salary of $10.00, while the female teachers earned $2.50 a month. Her parents and sister Marry attended the 1848 Rochester Woman’s Rights Convention held August 2.

Anthony’s experience with the teacher’s union, temperance and antislavery reforms and Quaker upbringing, laid fertile ground for a career in women’s rights reform to grow. The career would begin with an introduction to Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

On a street corner in Seneca Falls in 1851, Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and later Stanton recalled the moment: “There she stood with her good earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray silk, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly, and why I did not at once invite her home with me to dinner, I do not know.”

Meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton was probably the beginning of her interest in women’s rights, but it is Lucy Stone’s speech at the 1852 Syracuse Convention that is credited for convincing Susan to join the women’s rights movement.

In 1853 Susan campaigned for women's property rights in New York State, speaking at meetings, collecting signatures for petitions and lobbying the state legislature. She circulated petitions for married women's property rights and woman suffrage. She addressed the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1854 and urged more petition campaigns. In 1854 she wrote to Matilda Joslyn Gage that “I know slavery is the all-absorbing question of the day, still we must push forward this great central question, which underlies all others.”

By 1856 she became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters and distributing leaflets. She encountered hostile mobs, armed threats and things thrown at her. She was hung in effigy, and in Syracuse her image was dragged through the streets.

At the 1856 National Women’s Rights Convention, Susan served on the business committee and spoke on the necessity of the dissemination of printed matter on women’s rights. She named The Lily and The Woman’s Advocate, and said they had some documents for sale on the platform.

Stanton and Anthony founded the American Equal Rights Association and in 1868 became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. The masthead of the newspaper proudly displayed their motto, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.”

By 1869 Stanton, Anthony and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association and focused their efforts on a federal woman’s suffrage amendment. In an effort to challenge suffrage, Susan and her three sisters voted in the 1872 Presidential election. She was arrested and put on trial in the Ontario Courthouse, Canandaigua, NY. The judge instructed the jury to find her guilty without any deliberations, and imposed a $100 fine. When she refused to pay a $100 fine and court costs, the judge did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her chance of an appeal. An appeal would have allowed the suffrage movement to take the question of women’s voting rights to the Supreme Court, but it was not to be.

From 1881 to 1885, Anthony joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage in writing the History of Woman Suffrage. As a final tribute to Susan B. Anthony, the Nineteenth Amendment was named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. It was ratified in 1920.

Click HERE for more information.

Susan was born in Adams, MA. After the Anthony family moved to Rochester, NY in 1845, they became active in the antislavery movement. Antislavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where they were sometimes joined by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Later two of Anthony's brothers, Daniel and Merritt, were anti-slavery activists in the Kansas territory.

In 1848 Susan was working as a teacher in Canajoharie, NY and became involved with the teacher’s union when she discovered that male teachers had a monthly salary of $10.00, while the female teachers earned $2.50 a month. Her parents and sister Marry attended the 1848 Rochester Woman’s Rights Convention held August 2.

Anthony’s experience with the teacher’s union, temperance and antislavery reforms and Quaker upbringing, laid fertile ground for a career in women’s rights reform to grow. The career would begin with an introduction to Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

On a street corner in Seneca Falls in 1851, Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and later Stanton recalled the moment: “There she stood with her good earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray silk, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly, and why I did not at once invite her home with me to dinner, I do not know.”

Meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton was probably the beginning of her interest in women’s rights, but it is Lucy Stone’s speech at the 1852 Syracuse Convention that is credited for convincing Susan to join the women’s rights movement.

In 1853 Susan campaigned for women's property rights in New York State, speaking at meetings, collecting signatures for petitions and lobbying the state legislature. She circulated petitions for married women's property rights and woman suffrage. She addressed the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1854 and urged more petition campaigns. In 1854 she wrote to Matilda Joslyn Gage that “I know slavery is the all-absorbing question of the day, still we must push forward this great central question, which underlies all others.”

By 1856 she became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters and distributing leaflets. She encountered hostile mobs, armed threats and things thrown at her. She was hung in effigy, and in Syracuse her image was dragged through the streets.

At the 1856 National Women’s Rights Convention, Susan served on the business committee and spoke on the necessity of the dissemination of printed matter on women’s rights. She named The Lily and The Woman’s Advocate, and said they had some documents for sale on the platform.

Stanton and Anthony founded the American Equal Rights Association and in 1868 became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. The masthead of the newspaper proudly displayed their motto, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.”

By 1869 Stanton, Anthony and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association and focused their efforts on a federal woman’s suffrage amendment. In an effort to challenge suffrage, Susan and her three sisters voted in the 1872 Presidential election. She was arrested and put on trial in the Ontario Courthouse, Canandaigua, NY. The judge instructed the jury to find her guilty without any deliberations, and imposed a $100 fine. When she refused to pay a $100 fine and court costs, the judge did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her chance of an appeal. An appeal would have allowed the suffrage movement to take the question of women’s voting rights to the Supreme Court, but it was not to be.

From 1881 to 1885, Anthony joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage in writing the History of Woman Suffrage. As a final tribute to Susan B. Anthony, the Nineteenth Amendment was named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. It was ratified in 1920.

Click HERE for more information.

The 19th Amendment

|

| Governor Edwin P. Morrow signing the Anthony Amendment. Kentucky was the 24th state to ratify on 6 Jan 1920. |

Thursday, January 23, 2014

Annie Besant (1847-1933)

"Better remain silent, better not even think, if you are not prepared to act." ~Annie Besant

Annie Morris, the daughter of William Wood and Emily Morris, was born in 1847 in London, Enland. Her father, a doctor, died when she was only five years old. Without any savings, Annie's mother found work looking after boarders at Harrow School. Mrs. Wood was unable to care for Annie and persuaded a friend, Ellen Marryat, who lived in Charmouth in Dorset, to take responsibility for her upbringing.

In 1866 Annie met the Rev. Frank Besant. Although only 19, she agreed to marry the young clergyman in Hastings on 21 Dec 1867. By the time she was 23 Annie had two children and was deeply unhappy because her independent spirit clashed with the traditional views of her husband. She also began to question her religious beliefs. When Annie refused to attend communion, Frank Besant ordered her to leave the family home after which a legal separation was arranged. Their son Digby stayed with Frank and daughter Mabel went to live with Annie in London.

After leaving her husband Annie completely rejected Christianity, and in 1874 joined the Secular Society. She soon developed a close relationship with Charles Bradlaugh, editor of the radical National Reformer and leader of the secular movement in Britain. Bradlaugh gave Annie a job working for the National Reformer and during the next few years wrote many articles on issues such as marriage and women's rights.

Annie also developed a reputation as an outstanding public speaker. The Irish journalist, T. P. O'Connor wrote: " What a beautiful and attractive and irresistible creature she was then, with her slight but full and well-shaped figure, her dark hair, her finely chiselled features… with that short upper lip that seemed always in a pout". Beatrice Webb claimed that she was the "only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion."

Tom Mann agreed: "The first time I heard Mrs. Besant was in Birmingham, about 1875. The only women speakers I had heard before this were of mediocre quality. Mrs. Besant transfixed me; her superb control of voice, her whole-souled devotion to the cause she was advocating, her love of the down-trodden, and her appeal on behalf of a sound education for all children, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, resolved that I would ascertain more correctly the why and wherefore of her creed."

In 1877 Annie and Charles Bradlaugh decided to publish The Fruits of Philosophy by Charles Knowlton, a book that advocated birth control. Annie and Bradlaugh were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences". In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." Besant and Bradlaugh were both found guilty of publishing an "obscene libel" and sentenced to six months in prison. At the Court of Appeal the sentence was quashed.

After the court-case Annie wrote and published her own book advocating birth control entitled The Laws of Population. The idea of a woman advocating birth-control received wide-publicity. Newspapers like The Times accused her of writing "an indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy and obscene book". Rev. Besant used the publicity of the case to persuade the courts that he, rather than Annie, should have custody of their daughter Mabel.

In 1880 Charles Bradlaugh was elected MP for Northampton, but as he was not a Christian he refused to take the oath, and was expelled from the House of Commons. As well as working with Bradlaugh, Annie also became friends with socialists such as Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and George Bernard Shaw. This upset Bradlaugh, who regarded socialism as a disruptive foreign doctrine.

After joining the Social Democratic Federation, Annie started her own campaigning newspaper called The Link. Like Catherine Booth of the Salvation Army, Annie was concerned about the health of young women workers at the Bryant & May match factory. On 23 Jun 1888, Annie published an article White Slavery in London where she drew attention to the dangers of phosphorus fumes and complained about the low wages paid to the women who worked at Bryant & May.

Three women who provided information for Annie's article were sacked. Annie responded by helping the women at Bryant & May to form a Matchgirls Union. After a three week strike, the company was forced to make significant concessions including the re-employment the three victimized women.

Annie also join the socialist group, the Fabian Society, and in 1889 contributed to the influencial book, Fabian Essays. As well as Besant, the book included articles by George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Webb, Sydney Olivier, Graham Wallas, William Clarke and Hubert Bland. Edited by Shaw, the book sold 27,000 copies in two years.

In 1889 Annie was elected to the London School Board. After heading the poll with a 15,000 majority over the next candidate, she argued that she had been given a mandate for large-scale reform of local schools. Some of her many achievements included a program of free meals for undernourished children and free medical examinations for all those in elementary schools.

In the 1890s Annie became a supporter of Theosophy, a religious movement founded by Helena Blavatsky in 1875. Theosophy was based on Hindu ideas of karma and reincarnation with nirvana as the eventual aim. She went to live in India but remained interested in the subject of women's rights. She continued to write letters to British newspapers arguing the case for women's suffrage and in 1911 was one of the main speakers at an important NUWSS rally in London.

While in India, Annie joined the struggle for Indian Home Rule, and during the First World War was interned by the British authorities. She died in India on 20 Sep 1933.

After leaving her husband Annie completely rejected Christianity, and in 1874 joined the Secular Society. She soon developed a close relationship with Charles Bradlaugh, editor of the radical National Reformer and leader of the secular movement in Britain. Bradlaugh gave Annie a job working for the National Reformer and during the next few years wrote many articles on issues such as marriage and women's rights.

Annie also developed a reputation as an outstanding public speaker. The Irish journalist, T. P. O'Connor wrote: " What a beautiful and attractive and irresistible creature she was then, with her slight but full and well-shaped figure, her dark hair, her finely chiselled features… with that short upper lip that seemed always in a pout". Beatrice Webb claimed that she was the "only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion."

Tom Mann agreed: "The first time I heard Mrs. Besant was in Birmingham, about 1875. The only women speakers I had heard before this were of mediocre quality. Mrs. Besant transfixed me; her superb control of voice, her whole-souled devotion to the cause she was advocating, her love of the down-trodden, and her appeal on behalf of a sound education for all children, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, resolved that I would ascertain more correctly the why and wherefore of her creed."

In 1877 Annie and Charles Bradlaugh decided to publish The Fruits of Philosophy by Charles Knowlton, a book that advocated birth control. Annie and Bradlaugh were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences". In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." Besant and Bradlaugh were both found guilty of publishing an "obscene libel" and sentenced to six months in prison. At the Court of Appeal the sentence was quashed.

After the court-case Annie wrote and published her own book advocating birth control entitled The Laws of Population. The idea of a woman advocating birth-control received wide-publicity. Newspapers like The Times accused her of writing "an indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy and obscene book". Rev. Besant used the publicity of the case to persuade the courts that he, rather than Annie, should have custody of their daughter Mabel.

In 1880 Charles Bradlaugh was elected MP for Northampton, but as he was not a Christian he refused to take the oath, and was expelled from the House of Commons. As well as working with Bradlaugh, Annie also became friends with socialists such as Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and George Bernard Shaw. This upset Bradlaugh, who regarded socialism as a disruptive foreign doctrine.

After joining the Social Democratic Federation, Annie started her own campaigning newspaper called The Link. Like Catherine Booth of the Salvation Army, Annie was concerned about the health of young women workers at the Bryant & May match factory. On 23 Jun 1888, Annie published an article White Slavery in London where she drew attention to the dangers of phosphorus fumes and complained about the low wages paid to the women who worked at Bryant & May.

Three women who provided information for Annie's article were sacked. Annie responded by helping the women at Bryant & May to form a Matchgirls Union. After a three week strike, the company was forced to make significant concessions including the re-employment the three victimized women.

Annie also join the socialist group, the Fabian Society, and in 1889 contributed to the influencial book, Fabian Essays. As well as Besant, the book included articles by George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Webb, Sydney Olivier, Graham Wallas, William Clarke and Hubert Bland. Edited by Shaw, the book sold 27,000 copies in two years.

In 1889 Annie was elected to the London School Board. After heading the poll with a 15,000 majority over the next candidate, she argued that she had been given a mandate for large-scale reform of local schools. Some of her many achievements included a program of free meals for undernourished children and free medical examinations for all those in elementary schools.

In the 1890s Annie became a supporter of Theosophy, a religious movement founded by Helena Blavatsky in 1875. Theosophy was based on Hindu ideas of karma and reincarnation with nirvana as the eventual aim. She went to live in India but remained interested in the subject of women's rights. She continued to write letters to British newspapers arguing the case for women's suffrage and in 1911 was one of the main speakers at an important NUWSS rally in London.

While in India, Annie joined the struggle for Indian Home Rule, and during the First World War was interned by the British authorities. She died in India on 20 Sep 1933.

Amelia Bloomer (1818-1894)

"As soon as it became known that I was wearing the new dress, letters came pouring in upon me by the hundreds from women all over the country making inquiries about the dress and asking for patterns—showing how ready and anxious women were to throw off the burden of long, heavy skirts." ~Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Jenks was born on 27 May 1818 in Homer, NY. At the age of 22 she married attorney Dexter Bloomer, who encouraged her to write for his New York newspaper, the Seneca Falls County Courier.

In 1848, Amelia attended the Seneca Falls Convention, an influential women's rights convention in the U.S. The following year, she began editing the first newspaper for women, The Lily. It was published biweekly from 1849 until 1853. The newspaper began as a temperance journal, but came to have broad mix of contents ranging from recipes to moralist tracts, particularly when influenced by temperance activist and suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Amelia felt that because women lecturers were considered unseemly, writing was the best way for women to work for reform. Originally, The Lily was to be for “home distribution” among members of the Seneca Falls Ladies Temperance Society, which had formed in 1848, and eventually had a circulation of over 4,000. The paper encountered several obstacles early on, and the Society’s enthusiasm died out. Bloomer felt a commitment to publish and assumed full responsibility for editing and publishing the paper. Originally, the title page had the legend “Published by a committee of ladies.” But after 1850 – only Bloomer’s name appeared on the masthead. This newspaper was a model for later periodicals focused on women's suffrage.

Amelia described her experience as the first woman to own, operate and edit a news vehicle for women:

"It was a needed instrument to spread abroad the truth of a new gospel to woman, and I could not withhold my hand to stay the work I had begun. I saw not the end from the beginning and dreamed where to my propositions to society would lead me."

In her publication, she promoted a change in dress standards for women that would be less restrictive in regular activities:

In her publication, she promoted a change in dress standards for women that would be less restrictive in regular activities:

"The costume of women should be suited to her wants and necessities. It should conduce at once to her health, comfort, and usefulness; and, while it should not fail also to conduce to her personal adornment, it should make that end of secondary importance."

In 1851, New England temperance activist Elizabeth Smith Miller (aka Libby Miller) adopted what she considered a more rational costume: loose trousers gathered at the ankles, like women's trousers worn in the Middle East and Central Asia, topped by a short dress or skirt and vest. The costume was worn publicly by actress Fanny Kemble. Miller displayed her new clothing to Stanton, her cousin, who found it sensible and becoming, and adopted it immediately. In this garb Stanton visited Bloomer, who began to wear the costume and promote it enthusiastically in her magazine. Articles on the clothing trend were picked up in the New York Tribune. More women wore the fashion which was promptly dubbed "The Bloomer Costume" or "Bloomers". However, the bloomers were subjected to ceaseless ridicule in the press and harassment on the street. Amelia herself dropped the fashion in 1859, saying that a new invention, the crinoline, was a sufficient reform that she could return to conventional dress.

Amelia remained a suffrage pioneer and writer throughout her life, writing for a wide array of periodicals. Although she was far less famous than some other suffragettes, she made many significant contributions to the women’s movement — particularly concerning dress reform and the temperance movement. She led suffrage campaigns in Nebraska and Iowa, and served as president of the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association from 1871 until 1873.

Amelia died on 30 Dec 1894 in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

Madeline McDowell Breckinridge (1872-1920)

Madeline "Madge" McDowell Breckinridge was a leader of the women's suffrage movement and one of Kentucky's leading progressive reformers.

She was born in Woodlake, KY on 20 May 1872 and grew up in Ashland at the Henry Clay Estate, a farm established by her great-grandfather, 19th century statesman Henry Clay. Her mother was Henry Clay, Jr.'s daughter, Anne Clay, and her father was Maj. Henry Clay McDowell (a namesake of Henry Clay), who served during the American Civil War on the Union side.

She was educated in Lexington, KY, at Miss Porter's School in Farmington, CT and at State College (now the University of Kentucky) intermittently between 1890-1894. In 1898 Madeline married Desha Breckinridge, the editor of the Lexington Herald and a brother of the pioneering social worker Sophonisba Breckinridge. The Breckinridges together used the newspaper's editorial pages to promote political and social causes of the Progressive Era, especially programs for the poor, child welfare and for women's rights.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed shortly before she died. She was able to vote only once in her life, in the November 1920 presidential election, before suffering a stroke and dying on Thanksgiving day, 25 Nov 1920.

She was educated in Lexington, KY, at Miss Porter's School in Farmington, CT and at State College (now the University of Kentucky) intermittently between 1890-1894. In 1898 Madeline married Desha Breckinridge, the editor of the Lexington Herald and a brother of the pioneering social worker Sophonisba Breckinridge. The Breckinridges together used the newspaper's editorial pages to promote political and social causes of the Progressive Era, especially programs for the poor, child welfare and for women's rights.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed shortly before she died. She was able to vote only once in her life, in the November 1920 presidential election, before suffering a stroke and dying on Thanksgiving day, 25 Nov 1920.

Lucy Burns (1879-1966)

Born to an Irish Catholic family in Brooklyn, NY on 28 Jul 1879, Lucy was a brilliant student of language and linguistics. She studied at Vassar College and Yale University in the United States and at the University of Berlin in Germany (1906-8). While a student at Oxford College in Cambridge, England, she witnessed the militancy of the British suffrage movement.

She set her academic goals aside and in 1909 became an activist with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She perfected the art of street speaking, was arrested repeatedly, and was imprisoned four times. From 1910 to 1912 she worked as a suffrage organizer in Scotland.

Lucy met Alice Paul in a London police station after both were arrested during a suffrage demonstration outside Parliament. Their alliance was powerful and long-lasting. Returning to the United States (Paul in 1910, Burns in 1912), the two women worked first with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) as leaders of its Congressional Committee. In April 1913 they founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), which evolved into the NWP. Burns organized campaigns in the West (1914, 1916), served as NWP legislative chairman in Washington, D.C., and, beginning in April 1914, edited the organization's weekly journal, The Suffragist.

She was a driving force behind the picketing of President Woodrow Wilson's administration in Washington, DC, beginning in January 1917. Six months later, she and Dora Lewis–targeting the attention of visiting Russian envoys–attracted controversy by prominently displaying a banner outside the White House declaring that America was not a free democracy as long as women were denied the vote. When Lucy participated in a similar action with Katharine Morey later the same month, they were arrested for obstructing traffic. The banners displeased President Wilson and escalated the administration's response to the picketing.

|

| At Occoquan Workhouse |

An expanded biography can be found HERE.

Lillie Devereau Blake (1833-1913)

"We are tired of the pretense that we have special privileges and the reality that we have none; of the fiction that we are queens, and the fact that we are subjects; of the symbolism which exalts our sex but is only a meaningless mockery." ~Lillie Devereau Blake

Lillie Devereux Blake (August 12, 1833–December 30, 1913) was an American woman suffragist and reformer, born in Raleigh, North Carolina, and educated in New Haven, Connecticut.

Born Elizabeth Johnson Devereux to George Pollock Devereux and Sarah Elizabeth Johnson, she spent much of her early childhood in Roanoke, Virginia. It was George Devereux who called his daughter "Lilly," giving her the name she would later adopt as her own. Her father, a plantation owner in North Carolina, died in 1837. At this point, Sarah Elizabeth Johnson took her two daughters and moved back to her family in Connecticut. Lillie grew up in New Haven, Connecticut where she studied at Miss Apthorp's school for girls before receiving further education from Yale tutors.

Lillie’s close connection to Yale turned into a minor scandal. She was a renowned belle, who at 16 wrote that she intended to redress the wrongs done to her sex by trifling with men’s hearts. Although she abandoned this particular formulation of feminism, the difficulties of expressing her independence within the limited roles allowed by her social station would prove a continuing theme in her life. In this case, a Yale undergraduate was expelled for being involved with her in what was called a disgraceful affair. The student was an admirer whose affections were too serious. She rejected him and he retaliated with stories implying a sexual relationship. He was punished by the college for impugning her character. In her autobiography, Lillie Blake denied that a disgraceful affair had taken place and expressed regret that the student had been expelled. She also noted that the story was not taken very seriously in social circles as she still received offers of marriage.

In 1855 she married Frank G. Q. Umsted, a Phildelphia lawyer. Her first daughter was born in 1857; her second daughter was born the following year. Frank died in 1859 (after apparently committing suicide) leaving her with two children to support. Blake began to write feverishly to support herself and her daughters: she wrote short stories, novels, newspaper and magazine articles. Her first story, "A Lonely House", appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. In the next few years, she produced two successful novels, Southwold (1859) and Rockford (1862). What generated the most money and fame for Blake, however, was her job as a correspondent in Washington, DC during the Civil War. She was contracted as a correspondent for several publications, including the New York Evening Post, New York World, Philadelphia Press and Forney's War Press.

Blake’s early fiction modeled itself on the popular sentimental fiction of the time, but became subversive. Her stories for popular magazines, published under her own name and various noms de plum, depicted strong female protagonists in standard sentimental plots which reflected her own resistance to the roles that she was expected to fill in her own life. Her later fiction included the realism that she gained from her journalism experience. It also showed a more explicit consciousness of women’s issues. Her most famous novel Fettered for Life, or, Lord and Master: A Story of To-Day is an attempt to draw attention to the myriad of complex issues facing women.

In 1866 she married Grinfill Blake, a wealthy New York merchant. She was one of the active promoters of the movement that resulted in the founding of Barnard College. In 1869, she visited the Women's Bureau in New York and soon after, began speaking all over the United States in support of female enfranchisement. She earned a reputation as a freethinker and gained fame when she attacked the well known lectures of Morgan Dix, a clergyman who asserted that woman’s inferiority was supported by the Bible. Her lectures, published as Woman’s Place To-Day rejected this idea, asserting in one instance that if Eve was inferior to Adam because she was created after him, then by the same logic Adam was inferior to the fishes. Blake testified before the New York Constitutional Commission of 1873 in support for women's suffrage. Along with Matilda Joslyn Gage, she signed the 1876 Centennial Women's Rights Declaration. She was president of the New York State Woman's Suffrage Association from 1879 to 1890 and of the New York City Woman's Suffrage League from 1886 to 1900. Blake completely broke ties with the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1900 when Susan B. Anthony, who was retiring as the leader of the organization, selected Carrie Chapman Catt and Anna Howard to succeed her. Blake had withdrawn her candidacy in the interests of harmony. For years, Blake and Anthony had disagreed on the basic purpose of the women's movement. Anthony wanted to focus solely on suffrage; Blake wanted to pursue a broader course of reform. This split in strategy was caused by a deeper theoretical divide. Blake developed a theory of gender that was radical for her time. She argued that gender roles are learned behaviors, and that women and men shared a common nature. Therefore, women should have the same rights as men in all areas. Anthony and her followers instead emphasized the unique nature of women, their separate sphere, and innate moral authority as justification for their right to suffrage. This conflict, among others that Blake took part in, helps to explain the way she is remembered, or not remembered, in the context of the woman’s movement.

Born Elizabeth Johnson Devereux to George Pollock Devereux and Sarah Elizabeth Johnson, she spent much of her early childhood in Roanoke, Virginia. It was George Devereux who called his daughter "Lilly," giving her the name she would later adopt as her own. Her father, a plantation owner in North Carolina, died in 1837. At this point, Sarah Elizabeth Johnson took her two daughters and moved back to her family in Connecticut. Lillie grew up in New Haven, Connecticut where she studied at Miss Apthorp's school for girls before receiving further education from Yale tutors.

Lillie’s close connection to Yale turned into a minor scandal. She was a renowned belle, who at 16 wrote that she intended to redress the wrongs done to her sex by trifling with men’s hearts. Although she abandoned this particular formulation of feminism, the difficulties of expressing her independence within the limited roles allowed by her social station would prove a continuing theme in her life. In this case, a Yale undergraduate was expelled for being involved with her in what was called a disgraceful affair. The student was an admirer whose affections were too serious. She rejected him and he retaliated with stories implying a sexual relationship. He was punished by the college for impugning her character. In her autobiography, Lillie Blake denied that a disgraceful affair had taken place and expressed regret that the student had been expelled. She also noted that the story was not taken very seriously in social circles as she still received offers of marriage.

In 1855 she married Frank G. Q. Umsted, a Phildelphia lawyer. Her first daughter was born in 1857; her second daughter was born the following year. Frank died in 1859 (after apparently committing suicide) leaving her with two children to support. Blake began to write feverishly to support herself and her daughters: she wrote short stories, novels, newspaper and magazine articles. Her first story, "A Lonely House", appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. In the next few years, she produced two successful novels, Southwold (1859) and Rockford (1862). What generated the most money and fame for Blake, however, was her job as a correspondent in Washington, DC during the Civil War. She was contracted as a correspondent for several publications, including the New York Evening Post, New York World, Philadelphia Press and Forney's War Press.

Blake’s early fiction modeled itself on the popular sentimental fiction of the time, but became subversive. Her stories for popular magazines, published under her own name and various noms de plum, depicted strong female protagonists in standard sentimental plots which reflected her own resistance to the roles that she was expected to fill in her own life. Her later fiction included the realism that she gained from her journalism experience. It also showed a more explicit consciousness of women’s issues. Her most famous novel Fettered for Life, or, Lord and Master: A Story of To-Day is an attempt to draw attention to the myriad of complex issues facing women.

In 1866 she married Grinfill Blake, a wealthy New York merchant. She was one of the active promoters of the movement that resulted in the founding of Barnard College. In 1869, she visited the Women's Bureau in New York and soon after, began speaking all over the United States in support of female enfranchisement. She earned a reputation as a freethinker and gained fame when she attacked the well known lectures of Morgan Dix, a clergyman who asserted that woman’s inferiority was supported by the Bible. Her lectures, published as Woman’s Place To-Day rejected this idea, asserting in one instance that if Eve was inferior to Adam because she was created after him, then by the same logic Adam was inferior to the fishes. Blake testified before the New York Constitutional Commission of 1873 in support for women's suffrage. Along with Matilda Joslyn Gage, she signed the 1876 Centennial Women's Rights Declaration. She was president of the New York State Woman's Suffrage Association from 1879 to 1890 and of the New York City Woman's Suffrage League from 1886 to 1900. Blake completely broke ties with the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1900 when Susan B. Anthony, who was retiring as the leader of the organization, selected Carrie Chapman Catt and Anna Howard to succeed her. Blake had withdrawn her candidacy in the interests of harmony. For years, Blake and Anthony had disagreed on the basic purpose of the women's movement. Anthony wanted to focus solely on suffrage; Blake wanted to pursue a broader course of reform. This split in strategy was caused by a deeper theoretical divide. Blake developed a theory of gender that was radical for her time. She argued that gender roles are learned behaviors, and that women and men shared a common nature. Therefore, women should have the same rights as men in all areas. Anthony and her followers instead emphasized the unique nature of women, their separate sphere, and innate moral authority as justification for their right to suffrage. This conflict, among others that Blake took part in, helps to explain the way she is remembered, or not remembered, in the context of the woman’s movement.

Blake went on to create the National Legislative League. She worked on improving immigration laws for women and furthering equality in society. In addition, Blake helped establish pensions for Civil War nurses and also worked on granting mothers joint custody of their children. She wanted to have women involved in civic affairs and encouraged them to study law in school. She was the author of the law providing for matrons in the police stations, passed in 1891.

Blake was an avid writer and her writings also include: Fettered for Life (1872), a novel dealing with the woman's suffrage question; Woman's Place To-day (1883), a series of lectures in reply to Dr. Morgan Dix's lenten sermons on the Calling of a Christian Woman; and A Daring Experiment (1894).

Wednesday, January 22, 2014

Carrie Chapman Catt (1859-1947)

"To the wrongs that need resistance, To the right that needs assistance, To the future in the distance, Give yourselves." ~Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie was active in anti-war causes during the 1920s and 1930s. It was during this period that she became recognized as one of the most prominent female leaders of her time.

In 1933 in response to Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Carrie organized the Protest Committee of Non-Jewish Women Against the Persecution of Jews in Germany. This group gathered 9,000 signatures of non-Jewish American women and attached these to a letter of protest sent to Hitler in August 1933. The letter decried acts of violence and restrictive laws against German Jews. She pressured the U.S. government to ease immigration laws so that Jews could more easily take refuge in America. For her efforts, Catt became the first woman to receive the American Hebrew Medal. She also wrote the Do You know pamphlet, informing people about Woman Suffrage issues.

The last event Carrie helped organize was the Woman's Centennial Conference in New York in 1940, a celebration of the feminist movement in the United States. She died in New Rochelle in 1947.

Carrie Chapman Catt (January 9, 1859 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Associationand was the founder of the League of Women Voters and the International Alliance of Women. She "led an army of voteless women in 1919 to pressure Congress to pass the constitutional amendment giving them the right to vote and convinced state legislatures to ratify it in 1920" and "was one of the best-known women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century and was on all lists of famous American women".

Born Carrie Clinton Lane in Ripon, Wisconsin, she spent her childhood in Charles City, Iowa and graduated from Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames, Iowa, graduating in three years. Carrie became a teacher and then superintendent of schools in Mason City, Iowa in 1885 and was the first female superintendent of the district.

In 1885 Carrie married newspaper editor Leo Chapman, but he died soon after. Eventually she landed on her feet, but only after some harrowing experiences in the male working world. In 1890, she married George Catt, a wealthy engineer. Their marriage allowed her to spend a good part of each year on the road campaigning for women's suffrage, a cause she had become involved with in Iowa during the late 1880s. She also joined the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

Carrie became a close colleague of Susan B. Anthony, who selected Carrie to succeed her as head of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She was elected president of NAWSA twice; her first term was from 1900 to 1904 and her second term was from 1915 to 1920. Her second term coincided with the climax of the women's suffrage movement in the U.S. Under her leadership the movement focused on success in at least one eastern state, because previous to 1917 only western states had granted female suffrage. She thus led a successful campaign in New York state, which finally approved suffrage in 1917. During that same year President Wilson and the Congress entered World War I. Carrie made the controversial decision to support the war effort, which shifted the public's perception in favor of the suffragettes who were now perceived as patriotic. Receiving the support of President Wilson, the suffrage movement culminated in the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on 26 Aug 1920.

In her efforts to win women's suffrage state by state, Carrie sometimes appealed to the prejudices of the time. In South Dakota, she lamented that while women lacked suffrage, "The murderous Sioux is given the right to franchise which he is ready and anxious to sell to the highest bidder." In 1894, she urged that uneducated immigrants be stripped of their right to vote - the United States should "cut off the vote of the slums and give it to woman. White supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by women's suffrage," was her argument when trying to win over Mississippi and South Carolina in 1919.

NAWSA was by far the largest organization working for women's suffrage in the U.S. From her first endeavors in Iowa in the 1880s to her last in Tennessee in 1920, Carrie supervised dozens of campaigns, mobilized numerous volunteers (1 million by the end), and made hundreds of speeches. After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, she retired from NAWSA.

Carrie founded the League of Women Voters in 1920 as a successor to NAWSA. In the same year, she ran as the Presidential candidate for the ideologically Georgist Commonwealth Land Party.

She was also a leader of the international women's suffrage movement. She helped to found the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in 1902, serving as its president from 1904 until 1923. The IWSA remains in existence, now as the International Alliance of Women.

Born Carrie Clinton Lane in Ripon, Wisconsin, she spent her childhood in Charles City, Iowa and graduated from Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames, Iowa, graduating in three years. Carrie became a teacher and then superintendent of schools in Mason City, Iowa in 1885 and was the first female superintendent of the district.

In 1885 Carrie married newspaper editor Leo Chapman, but he died soon after. Eventually she landed on her feet, but only after some harrowing experiences in the male working world. In 1890, she married George Catt, a wealthy engineer. Their marriage allowed her to spend a good part of each year on the road campaigning for women's suffrage, a cause she had become involved with in Iowa during the late 1880s. She also joined the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

Carrie became a close colleague of Susan B. Anthony, who selected Carrie to succeed her as head of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She was elected president of NAWSA twice; her first term was from 1900 to 1904 and her second term was from 1915 to 1920. Her second term coincided with the climax of the women's suffrage movement in the U.S. Under her leadership the movement focused on success in at least one eastern state, because previous to 1917 only western states had granted female suffrage. She thus led a successful campaign in New York state, which finally approved suffrage in 1917. During that same year President Wilson and the Congress entered World War I. Carrie made the controversial decision to support the war effort, which shifted the public's perception in favor of the suffragettes who were now perceived as patriotic. Receiving the support of President Wilson, the suffrage movement culminated in the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on 26 Aug 1920.

In her efforts to win women's suffrage state by state, Carrie sometimes appealed to the prejudices of the time. In South Dakota, she lamented that while women lacked suffrage, "The murderous Sioux is given the right to franchise which he is ready and anxious to sell to the highest bidder." In 1894, she urged that uneducated immigrants be stripped of their right to vote - the United States should "cut off the vote of the slums and give it to woman. White supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by women's suffrage," was her argument when trying to win over Mississippi and South Carolina in 1919.

NAWSA was by far the largest organization working for women's suffrage in the U.S. From her first endeavors in Iowa in the 1880s to her last in Tennessee in 1920, Carrie supervised dozens of campaigns, mobilized numerous volunteers (1 million by the end), and made hundreds of speeches. After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, she retired from NAWSA.

Carrie founded the League of Women Voters in 1920 as a successor to NAWSA. In the same year, she ran as the Presidential candidate for the ideologically Georgist Commonwealth Land Party.

She was also a leader of the international women's suffrage movement. She helped to found the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in 1902, serving as its president from 1904 until 1923. The IWSA remains in existence, now as the International Alliance of Women.

Carrie was active in anti-war causes during the 1920s and 1930s. It was during this period that she became recognized as one of the most prominent female leaders of her time.

In 1933 in response to Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Carrie organized the Protest Committee of Non-Jewish Women Against the Persecution of Jews in Germany. This group gathered 9,000 signatures of non-Jewish American women and attached these to a letter of protest sent to Hitler in August 1933. The letter decried acts of violence and restrictive laws against German Jews. She pressured the U.S. government to ease immigration laws so that Jews could more easily take refuge in America. For her efforts, Catt became the first woman to receive the American Hebrew Medal. She also wrote the Do You know pamphlet, informing people about Woman Suffrage issues.

The last event Carrie helped organize was the Woman's Centennial Conference in New York in 1940, a celebration of the feminist movement in the United States. She died in New Rochelle in 1947.

Sunday, January 19, 2014

Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929)

"A large part of the present anxiety to improve the education of girls and women is also due to the conviction that the political disabilities of women will not be maintained." ~Millicent Fawcett

Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the daughter Newson Garrett and Louise Dunnell, was born in Aldeburgh, Suffolk in 1847. When she was twelve years old, her older sister, Elizabeth Garrett, moved to London in an attempt to qualify as a doctor. Millicent's visits to London to stay with her older sister Elizabeth and other sister, Louise, brought her into contact with people with radical political views. In 1865 Louise took Millicent to hear a speech on women's rights made by the Radical MP, John Stuart Mill. Millicent was deeply impressed by Mill and became one of his many loyal supporters.

Mill introduced Millicent to other campaigners for women's rights. This included Henry Fawcett, the Radical MP for Brighton. Fawcett, who had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1857, had been expected to marry Millicent's sister Elizabeth, but in 1865 she decided to concentrate of her attempts to become a doctor. Henry and Millicent became close friends and even though she was warned against marrying a disabled man, 14 years her senior, the couple was married in 1867. On 4 Apr 1868 their daughter, Philippa Fawcett, was born.

Over the next few years Millicent spent much of her time assisting Henry in his work as a MP However, Henry, an ardent supporter of women's rights, encouraged Millicent to continue her own career as a writer. At first Millicent wrote articles for journals but later books such as Political Economy for Beginners and Essays and Lectures on Political Subjects were published.

Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee in 1868. Although only a moderate public speaker, Millicent was a superb organizer and eventually emerged as the one of the leaders of the suffrage movement. She was so nervous before a speech that she was often physically ill. As a result she refused to make speeches more than four times a week.

She also campaigned against the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act: "In 1857 the Divorce Act was passed, and, as is well known, set up by law a different moral standard for men and women. Under this Act, which is still in force, a man can obtain the dissolution of the marriage if he can prove one act of infidelity on the part of his wife; but a woman cannot get her marriage dissolved unless she can prove that her husband has been guilty both of infidelity and cruelty."

Millicent also took a keen interest in women's education. She was involved in the organization of women's lectures at Cambridge that led to the establishment of Newnham College. Philippa Fawcett, went to Newnham and was placed first in the mathematical tripos.

The political career of Henry Fawcett was also going well. In 1880 William Gladstone, leader of the Liberal government, appointed Henry as his Postmaster General. Henry, who introduced the parcel post, postal orders and the sixpenny telegram, also used his power as Postmaster General to start employing women medical officers.

Henry was taken seriously ill with diphtheria and, although he gradually recovered, his political career had come to an end. Severely weakened by his illness, he died of pleurisy on 6 Nov 1884. It was claimed that "even decades later she would be visibly distressed by the mention of her husband's name."

Millicent now had more time for her own political career and became involved with the Personal Rights Association, which took an active role in exposing men who preyed on vulnerable young women. In 1886 she took part in a physical assault on an army major who had been pestering a servant of a friend of hers. According to William Stead: "They threw flour over his waxed moustache and in his eyes and down the back of his neck. They pinned a paper on his back, and made him the derision of a crowded street... in the sequel he was turned out of a club, and cut by a few lady friends - among them a young lady of some means to whom he was engaged at the time when he planned to ruin the country lass. Mrs Fawcett had no pity; she would have cashiered him if she could."

After the death of Lydia Becker in 1890, Millicent was elected president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She believed that it was important that the NUWSS campaigned for a wide variety of causes. This included helping Josephine Butler in her campaign against white slave traffic. Millicent also gave support to Clementina Black and her attempts to persuade the government to help protect low paid women workers.

Millicent's sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, joined the WSPU. In December, 1911 she wrote to her sister: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

Although Millicent had always been a Liberal, she became increasing angry at the party's unwillingness to give full support to women's suffrage. Herbert Asquith became Prime Minister in 1908. Unlike other leading members of the Liberal Party, Asquith was a strong opponent of votes for women. In 1912 Fawcett and the NUWSS took the decision to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary elections.

Despite Asquith's unwillingness to introduce legislation, Millicent remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. Like other members of the NUWSS, she feared that the militant actions of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) would alienate potential supporters of women's suffrage. However, Fawcett admired the courage of the suffragettes and was restrained in her criticism of the WSPU.

Millicent was upset when Louisa Garrett Anderson was sent to prison for taking part in the window-braking campaign. She wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does."

Mill introduced Millicent to other campaigners for women's rights. This included Henry Fawcett, the Radical MP for Brighton. Fawcett, who had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1857, had been expected to marry Millicent's sister Elizabeth, but in 1865 she decided to concentrate of her attempts to become a doctor. Henry and Millicent became close friends and even though she was warned against marrying a disabled man, 14 years her senior, the couple was married in 1867. On 4 Apr 1868 their daughter, Philippa Fawcett, was born.

Over the next few years Millicent spent much of her time assisting Henry in his work as a MP However, Henry, an ardent supporter of women's rights, encouraged Millicent to continue her own career as a writer. At first Millicent wrote articles for journals but later books such as Political Economy for Beginners and Essays and Lectures on Political Subjects were published.

Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee in 1868. Although only a moderate public speaker, Millicent was a superb organizer and eventually emerged as the one of the leaders of the suffrage movement. She was so nervous before a speech that she was often physically ill. As a result she refused to make speeches more than four times a week.

She also campaigned against the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act: "In 1857 the Divorce Act was passed, and, as is well known, set up by law a different moral standard for men and women. Under this Act, which is still in force, a man can obtain the dissolution of the marriage if he can prove one act of infidelity on the part of his wife; but a woman cannot get her marriage dissolved unless she can prove that her husband has been guilty both of infidelity and cruelty."

Millicent also took a keen interest in women's education. She was involved in the organization of women's lectures at Cambridge that led to the establishment of Newnham College. Philippa Fawcett, went to Newnham and was placed first in the mathematical tripos.

The political career of Henry Fawcett was also going well. In 1880 William Gladstone, leader of the Liberal government, appointed Henry as his Postmaster General. Henry, who introduced the parcel post, postal orders and the sixpenny telegram, also used his power as Postmaster General to start employing women medical officers.

Henry was taken seriously ill with diphtheria and, although he gradually recovered, his political career had come to an end. Severely weakened by his illness, he died of pleurisy on 6 Nov 1884. It was claimed that "even decades later she would be visibly distressed by the mention of her husband's name."

Millicent now had more time for her own political career and became involved with the Personal Rights Association, which took an active role in exposing men who preyed on vulnerable young women. In 1886 she took part in a physical assault on an army major who had been pestering a servant of a friend of hers. According to William Stead: "They threw flour over his waxed moustache and in his eyes and down the back of his neck. They pinned a paper on his back, and made him the derision of a crowded street... in the sequel he was turned out of a club, and cut by a few lady friends - among them a young lady of some means to whom he was engaged at the time when he planned to ruin the country lass. Mrs Fawcett had no pity; she would have cashiered him if she could."

After the death of Lydia Becker in 1890, Millicent was elected president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She believed that it was important that the NUWSS campaigned for a wide variety of causes. This included helping Josephine Butler in her campaign against white slave traffic. Millicent also gave support to Clementina Black and her attempts to persuade the government to help protect low paid women workers.

Millicent's sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, joined the WSPU. In December, 1911 she wrote to her sister: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

Although Millicent had always been a Liberal, she became increasing angry at the party's unwillingness to give full support to women's suffrage. Herbert Asquith became Prime Minister in 1908. Unlike other leading members of the Liberal Party, Asquith was a strong opponent of votes for women. In 1912 Fawcett and the NUWSS took the decision to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary elections.

Despite Asquith's unwillingness to introduce legislation, Millicent remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. Like other members of the NUWSS, she feared that the militant actions of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) would alienate potential supporters of women's suffrage. However, Fawcett admired the courage of the suffragettes and was restrained in her criticism of the WSPU.

Millicent was upset when Louisa Garrett Anderson was sent to prison for taking part in the window-braking campaign. She wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does."

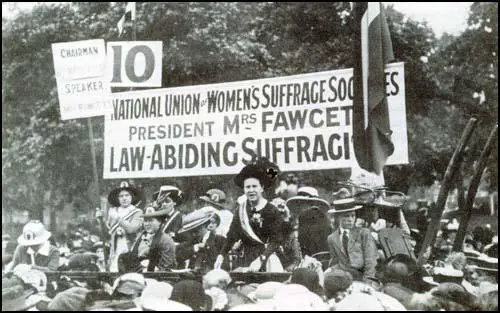

|

Millicent Fawcett addressing the crowds in

Hyde Park at the culmination of the Pilgrimage on

26 Jul 1913.

|